The art of navigating design in UK public sector digital projects – and why GDS standards feel so ambiguous

In UK government, policy intent increasingly lives or dies in the way digital services are designed and delivered. GDS standards and the Service Standard are meant to de‑risk that journey, but in practice they are interpreted very differently across programmes, departments and suppliers. For policy and delivery leaders, this ambiguity can quietly undermine both business cases and outcomes, even when projects appear “green” on paper. This article looks at where that ambiguity comes from and what leaders in government and suppliers can do to make design a more reliable lever for delivering policy and value.

Public sector transformation projects in the UK, especially those that impact the way services are consumed by users (whether citizens or employees), are generally expected to follow the standards described by the Government Digital Service (GDS). Projects executed by the National Health Service (NHS) or local government bodies often rely on the same standards for digital services that they own and manage. In a recent change, GDS has created a new local government unit to deliver more standardised and joined‑up services. The 14‑point Service Standard provides detailed guidelines on how to design and deliver a service by putting users’ needs first.

These services are regularly assessed at different phases of their lifecycle (from initial business case to go‑live) by assessors from different DDaT (Digital, Data and Technology) disciplines. They provide a RAG (Red‑Amber‑Green) status to confirm whether work has been done in line with the standard and where more evidence or rework is required before the service can move to the next phase.

There is high‑level guidance in the Service Manual on which projects generally require a service assessment. Some departments also apply their own discretion on whether to assess or exempt a project or a specific phase. The general rule is that if the service is high volume, high value, or significantly changes the way users access it, then it is likely to need an assessment. Government sees this as a way to ensure that heavily tech‑led projects are not blind‑sided by technology alone and remain grounded in user needs and business value at every stage. Treasury and departmental finance functions then use the results as one of the inputs when approving funding for the next phase of large transformation projects. GDS also regularly selects services for post go‑live audit to check whether live services are working in line with the Service Standard.

The Service Manual has been articulated to a reasonable level of detail and is supported by a wide community of practitioners and trained assessors who provide the underlying interpretation for successful adoption and implementation of the standard.

With such a large user base of practitioner‑followers, it would be reasonable to expect that adoption of these standards, widely termed as GDS standards, would be widespread and highly mature. In reality, the applicability of these standards across the public sector is varied and sits at very different maturity levels. One could argue that this is no different to other standards and therefore to be expected. However, this ambiguity affects the scope and clarity of the DDaT profession (and more specifically the UCD family of roles such as Service Design and User Research) and, consequently, the outcomes that government wants from sponsoring these projects. This variety in interpreting the GDS standards is precisely the motivation behind writing this blog post: to highlight the causes and issues that lead to such ambiguity and show how to successfully navigate user‑centred design work through such projects.

Let’s start first with the background of GDS to understand why and how it was initiated

GDS was set up in 2011, in the Cabinet Office, in response to the Martha Lane Fox “Directgov 2010 and beyond: revolution not evolution” review, which argued that government needed a single digital team with the authority to redesign services around user needs rather than departmental silos. Under Minister Francis Maude and its first Executive Director, Mike Bracken, GDS launched GOV.UK to replace thousands of separate department and agency sites, established the Service Standard and Design Principles, and positioned digital, data and technology as a core capability of government rather than something to be outsourced.

In its first year, GDS ran the “alphagov” experiment and built quick flagship products such as the online petitions service to prove that a new delivery model could work. GDS then replaced around 1,800 separate department and agency sites with the single GOV.UK domain, which went live in 2012 and cut running costs while simplifying access for users. Over time, this expanded into the “government as a platform” vision—common components, standards and platforms that all departments and, increasingly, the wider public sector can reuse. Back in 2018, I was lucky to work with Lou Downe while at Homes England and learn first‑hand some of the key principles of the Service Standard and how to work through them in large, complex government departments.

Reasons for ambiguity in public sector projects

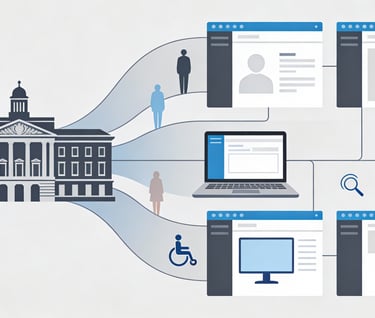

Delivering in the public sector requires more than a commercial mindset. Value is not just defined by the amount of money saved, but more importantly by the ability to provide an easily accessible service to users of all abilities. Users could be both external citizen users as well as professional or expert users, either from inside the department or from other external organisations. In the public sector, decisions on a business case for a digital (or service) transformation project are usually informed by policy-making through service design. In simple terms, Ministers and Civil Servants create an investment or improvement rationale and then leverage service design to understand the evidence and fine-tune the business case. Most departments have in-house service design and user research teams that are continuously engaged in supporting such policy-making aspects.

Ambiguity creeps in when policy goals have to be realised through a delivery transformation project. Examples of these are:

Lack of clarity over what defines a “service”

When the service transcends multiple departments or external bodies

Whether a service transformation activity falls under the remit of GDS/CDDO standards, and the extent of their applicability

Application of the Service Standard when deploying COTS (Commercial Off‑The‑Shelf) software, such as Oracle, Salesforce or Pega

When the technology has already been decided, and there is a tight timeline to deploy the service

When department leadership believes they can secure an exception

Interpretation of accessibility, inclusivity and equality within the service. This is especially important given that these attributes are underpinned by UK legislation and should not be taken lightly by project and departmental teams

For policy, SRO and supplier leadership, these ambiguities show up as scope creep, contested ownership and late design changes that increase risk and cost.

How to make Design work

Unfortunately, even after 15 years of GDS, it is still a tough sell to bake design into government service transformation projects. Based on my experience of delivering several such design activities as either a UCD or Service Design Lead, I have a few top tips to share on making design work.

Start at the highest and lowest levels of the programme at the same time

Planning at the highest level – Most service transformation programmes work to a high‑level plan and often underestimate the design work required to deliver successful services through different stages of the programme. A UCD lead must sit at the highest table to negotiate and insert key design milestones into the overall programme plan.

For programme boards and SROs, this means explicitly commissioning a UCD lead role, with a clear mandate, budget and milestones in the delivery roadmap, not just “we’ll involve design later”.

Working at the lowest level – Ensure that there is a Service Designer and/or User Researcher embedded within each project (service) team to challenge the evolving unit of work (user stories, epics, features, business case, prioritisation list, solution documents) through a user lens. These should be adequately evidenced against user needs before passing to the next phase of the programme or project.

For supplier engagement and contracting, this means baking UCD roles and deliverables into statements of work and acceptance criteria, rather than treating them as optional extras.

Reminding everyone of the GDS assessment can provide useful support, but it also risks turning user‑centred design activity into a “dress‑up” exercise done purely to pass the assessment. The intent should not be to keep harping on about the assessment threat but to focus on real user needs and to remind teams of the risks if those needs are not met.

Not all user needs can be met on day one, so rationality and pragmatism from the design team is essential to work in step with the rest of the project and service team. It becomes vital to demonstrate that the design team is as business‑ and tech‑savvy as others, while keeping a razor‑sharp eye on user needs and the value they deliver through the course of the program and not just for a few months or weeks only.

None of this is fixable by designers alone; it needs explicit sponsorship from policy, SRO and supplier leadership to give design the mandate and the space to operate.

What can you do as a UCD or non-UCD professional in public sector

This guidance applies to both UCD and non-UCD professionals to make design work successfully as achieving the service standard is a common goal for everyone and not just that odd UCD professional. So what would you do?

If you are one of the UCD professionals such as a Service Designer, User Researcher, Interaction Designer, Content Designer or Accessibility specialist, make sure you are thinking from the lens of design rather than staying within your own professional limits. In today’s AI‑led, multi‑domain technology landscape, UCD increasingly looks like a single discipline that needs to understand the tech well enough to keep pace with the language the rest of the programme uses.

While it is important to keep educating others about UCD roles, it is sometimes more pragmatic to deliver the message wrapped up in the language that the rest of the programme understands. For example, show the risk, impact and business value of design activities in terms that align with programme outcomes.

If you are a non‑UCD professional such as a Business Analyst, Enterprise Architect, Delivery Manager, Tester or Developer, engage design professionals in the key decisions of the project so you have assurance that technical activities and outcomes are underpinned by user needs where appropriate. Question yourself first about whether a user lens would be helpful for any given technical outcome. Do not wait until the end of the process to seek help; instead, proactively involve design at the start so that design professionals have the time and space to plan the right interventions and help you deliver the service to the original timeline.

If you are a delivery or policy leader in government or a leader in an IT consultancy or supplier, it is important that you see UCD or design as a critical enabler of service success rather than a “nice to have”. The benefits go well beyond meeting the Service Standard: trade unions are more likely to be supportive, there is less risk of complaints, reputational risk is reduced, and business value realisation is stronger overall.

For Public Sector Leaders treat the Service Standard like a governance and assurance tool, not an after‑the‑fact gateway. Sponsor design early as a way of de‑risking policy delivery, not just as a compliance activity.

For IT Suppliers, position your design capability as a way to reduce delivery risk and increase benefit realisation for your client’s business case, not just as additional resource days on the plan.